Monica Majoli

Space of the Line: Ben, Rameses, Tom

09.12.23 – 10.14.23

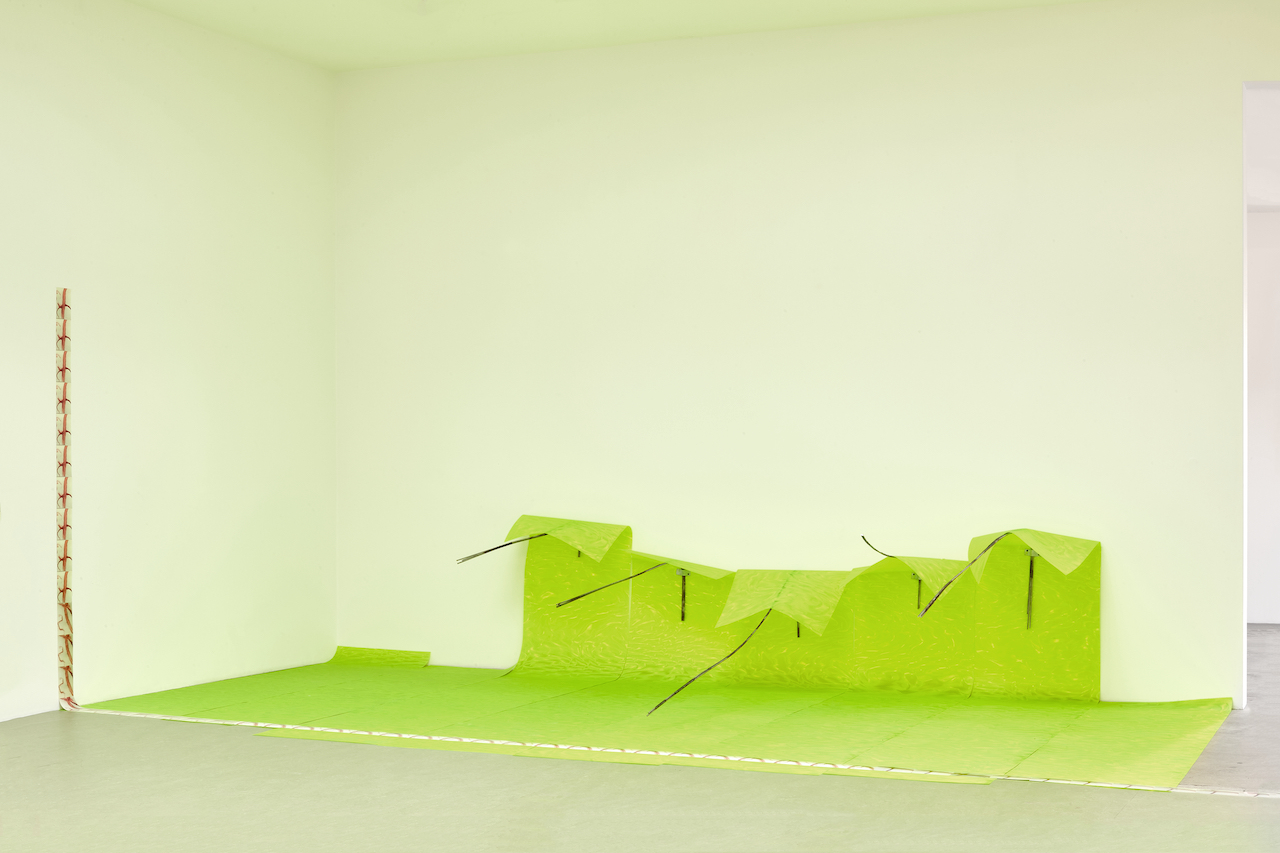

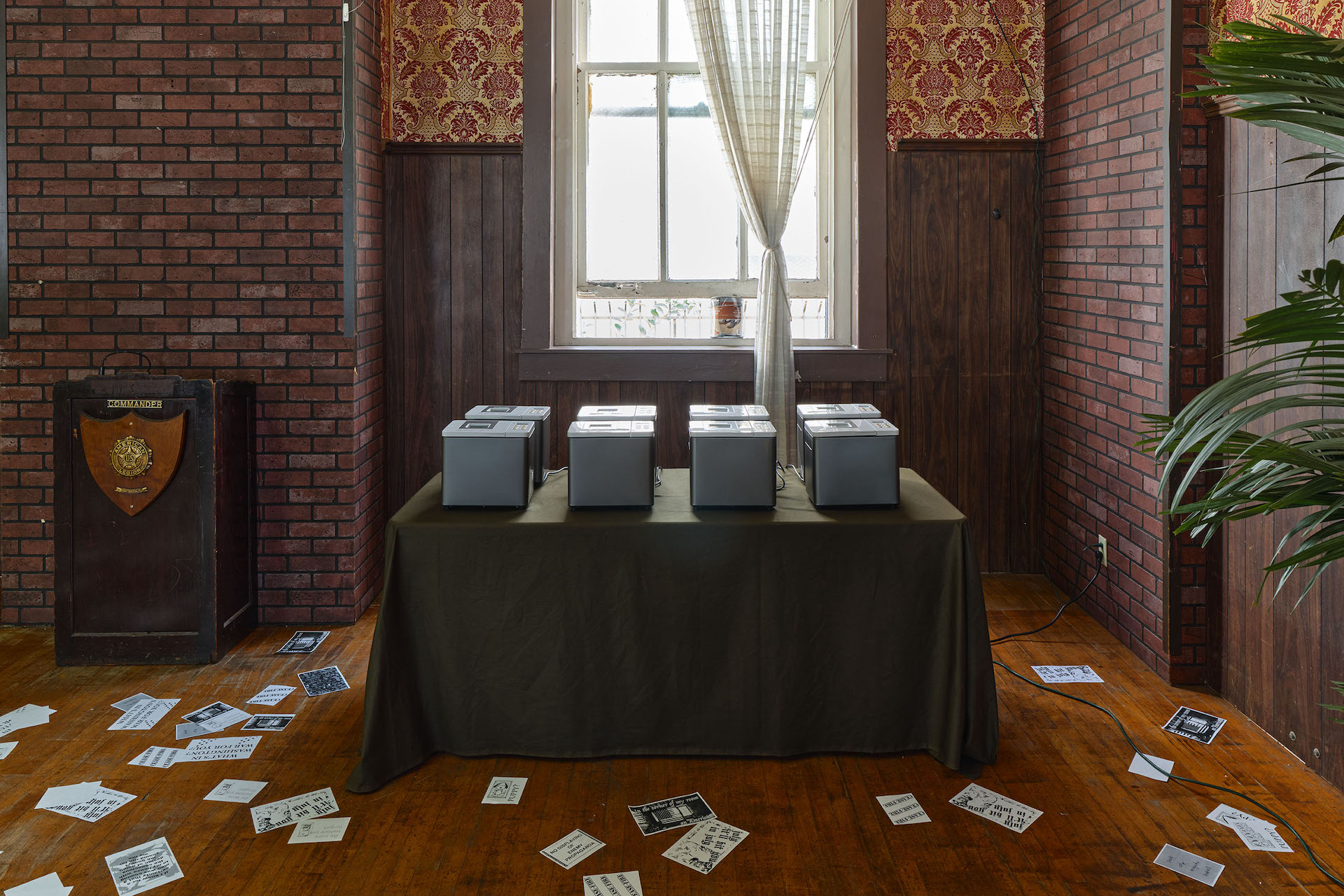

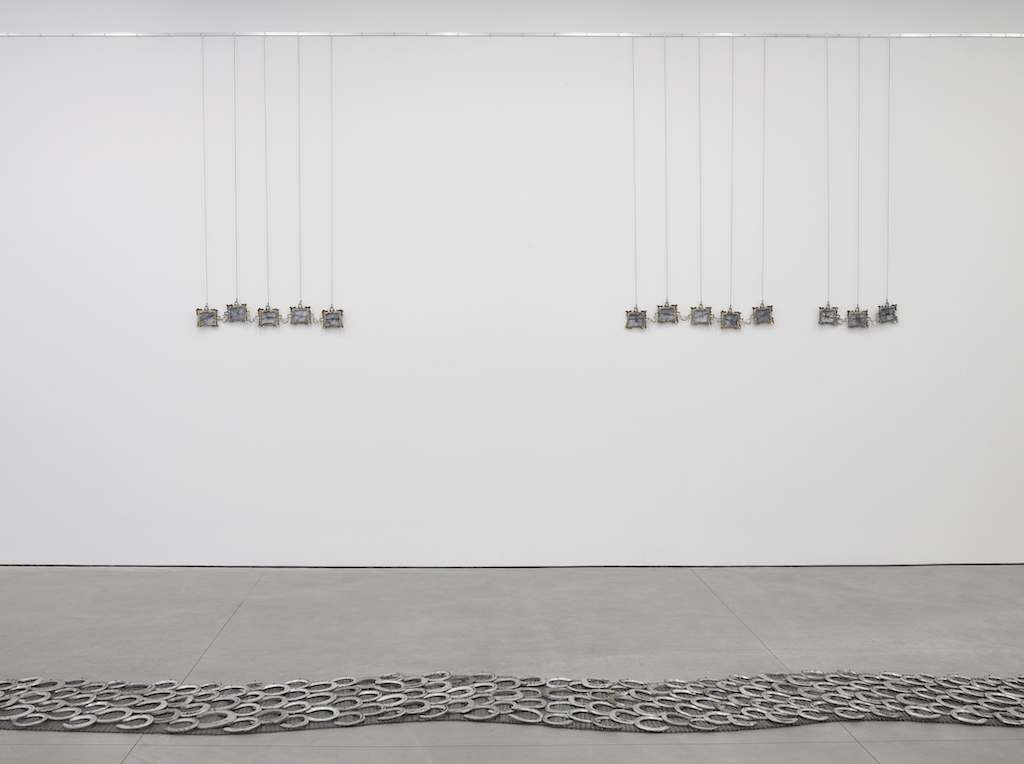

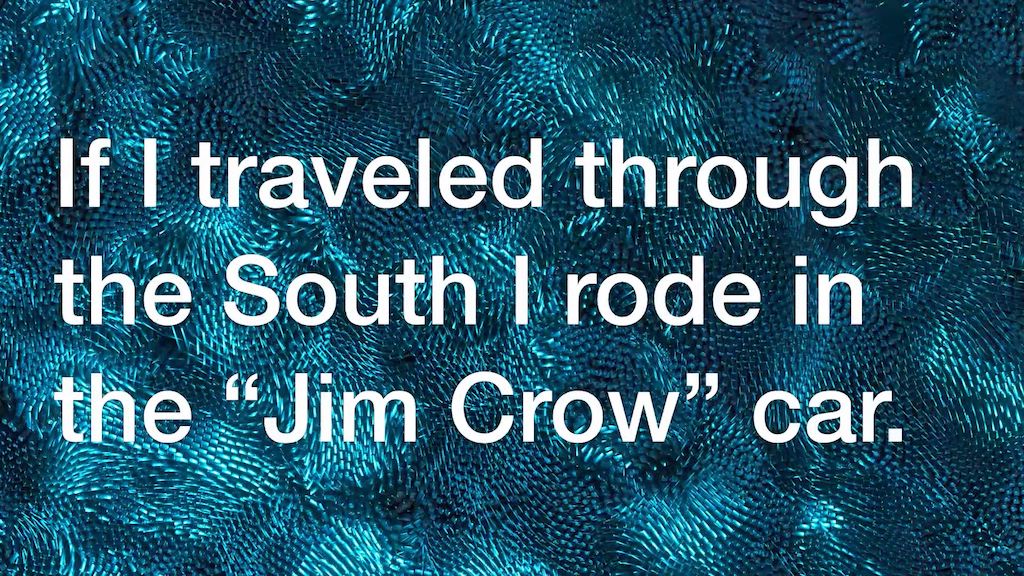

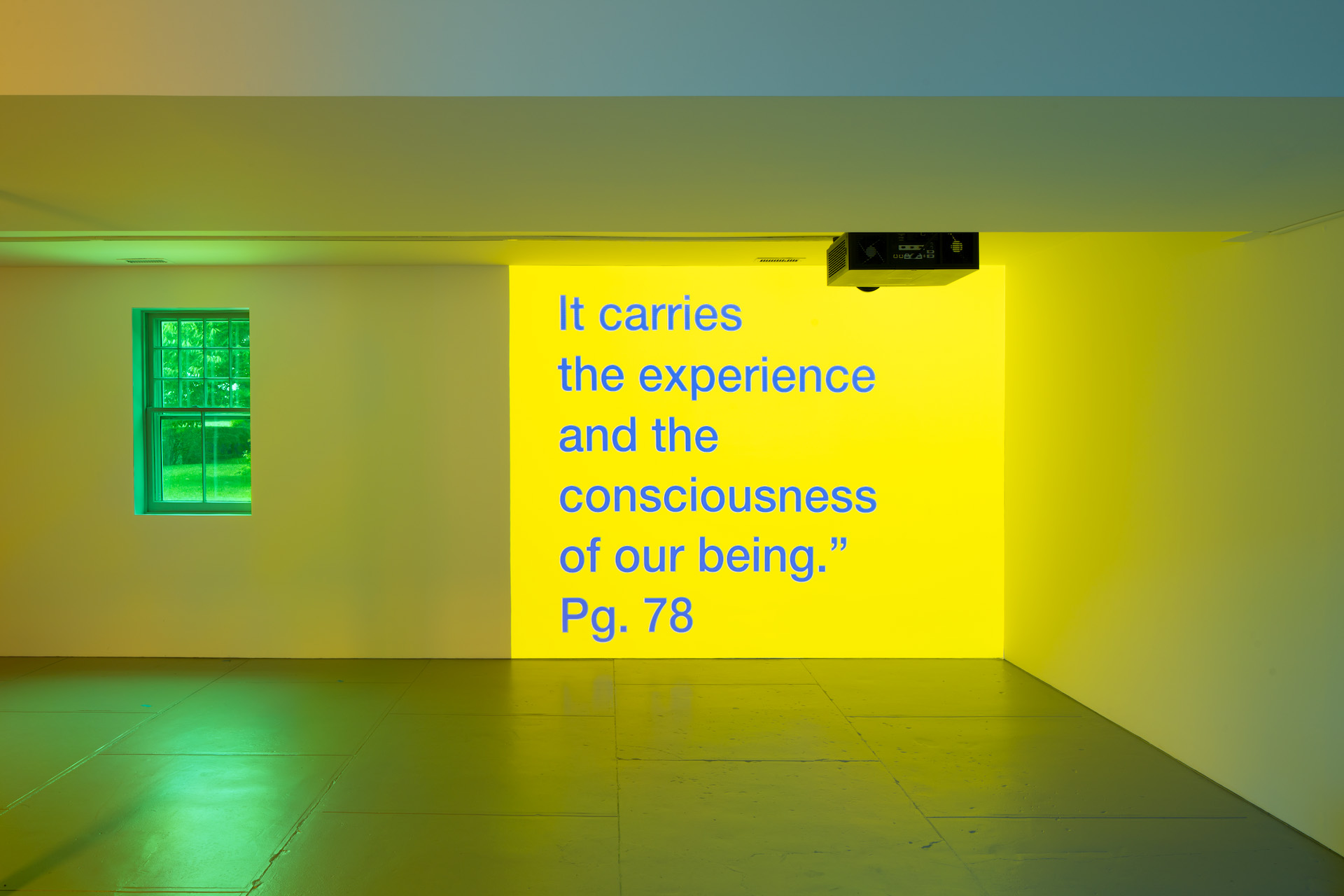

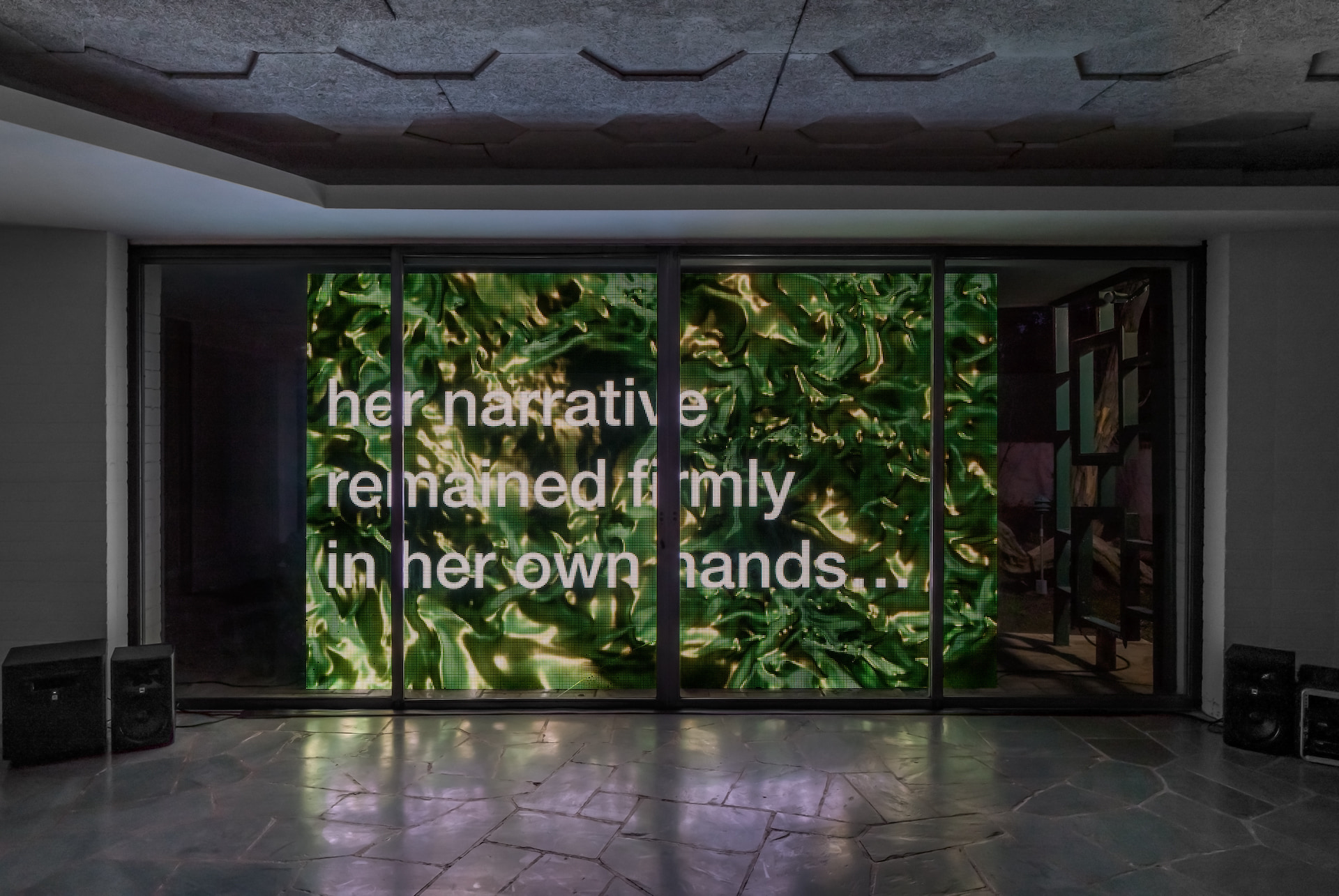

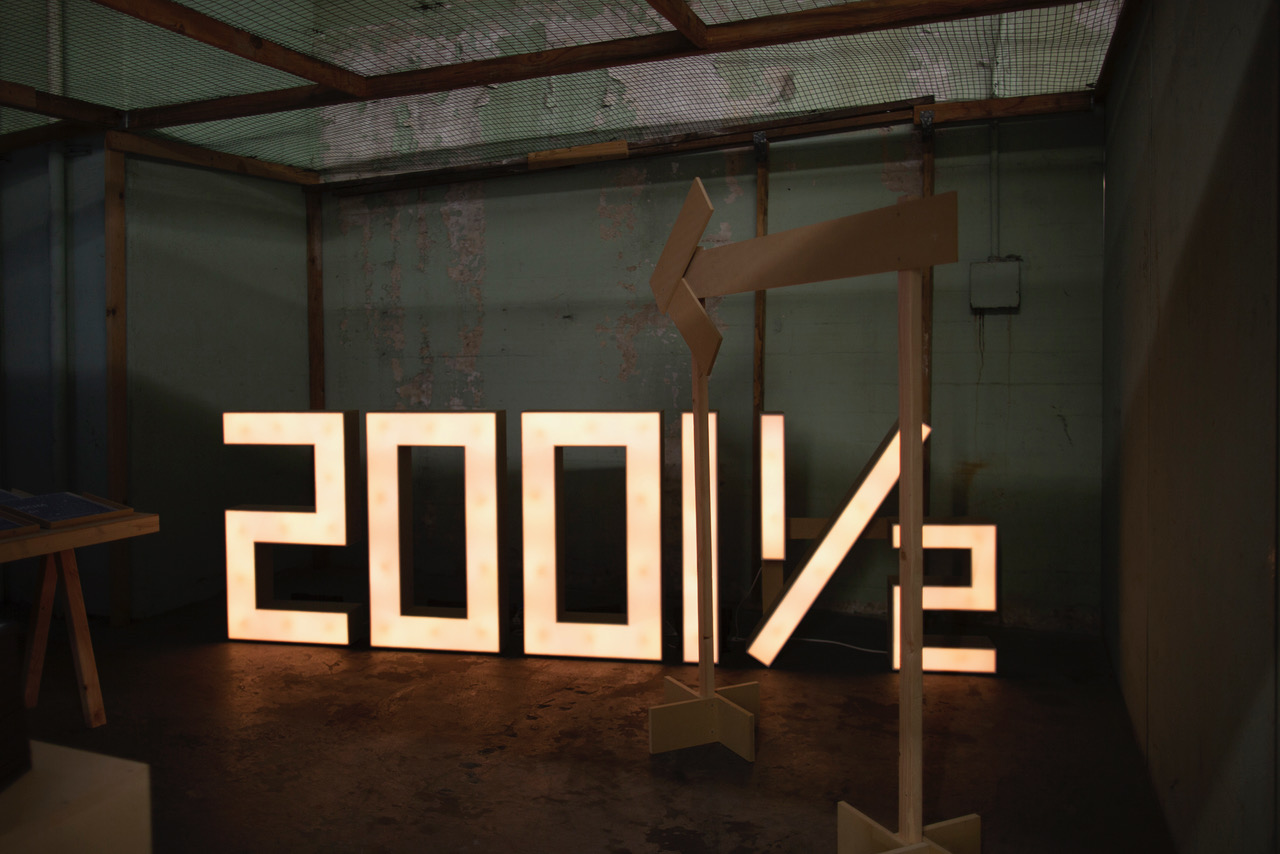

Installation view: Monica Majoli, Space of the Line: Ben, Rameses, Tom. 09.12.23 – 10.14.23

Installation view: Monica Majoli, Space of the Line: Ben, Rameses, Tom. 09.12.23 – 10.14.23

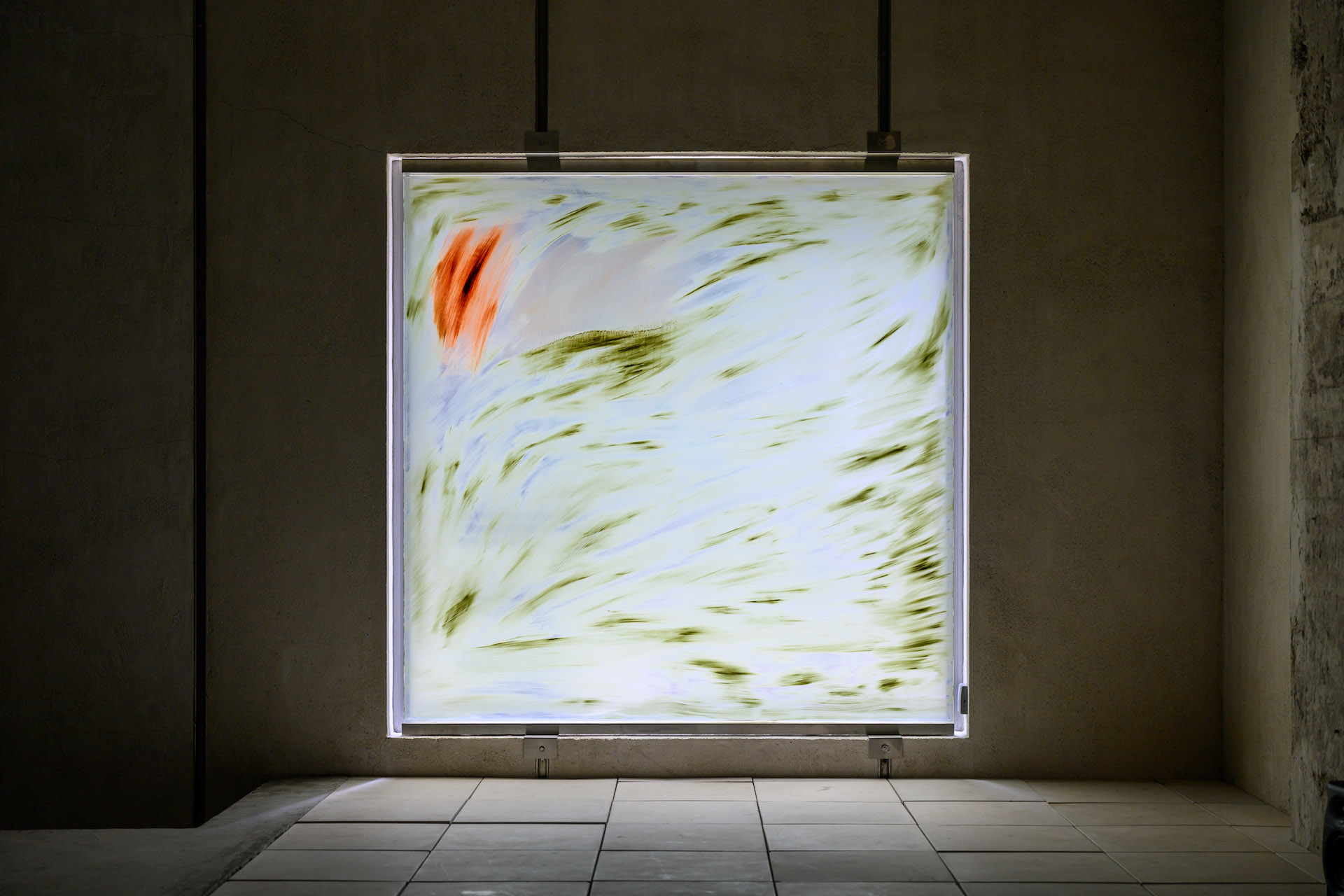

Monica Majoli, Playguy (Ben), 2023. Watercolor woodcut transfer on paper. Framed dimensions: 54 1/2 x 78 3/8 inches (138.4 x 199.1 cm)

Installation view: Monica Majoli, Space of the Line: Ben, Rameses, Tom. 09.12.23 – 10.14.23

Installation view: Monica Majoli, Space of the Line: Ben, Rameses, Tom. 09.12.23 – 10.14.23

Monica Majoli, Blueboy (Rameses), 2023. Watercolor woodcut transfer on paper. Framed dimensions: 72 3/8 x 61 1/2 inches (183.8 x 156.2 cm)

Installation view: Monica Majoli, Space of the Line: Ben, Rameses, Tom. 09.12.23 – 10.14.23

Installation view: Monica Majoli, Space of the Line: Ben, Rameses, Tom. 09.12.23 – 10.14.23

Monica Majoli, Blueboy (Tom), 2023. Watercolor woodcut transfer on paper. Framed dimensions: 56 x 80 3/4 inches (142.2 x 205.1 cm)

Exhibition information

‘We will end up less than sketches,’ Amy Gerstler once wrote, perfectly concerned with life’s fraught relationship to the line. Like so, Monica Majoli intuits contour as what’s impressed onto history, knowing, all the same, that few lives settle as record. She knows, that is, that here we are in the world with our anatomical hearts weighing us down with all that’s seen and felt, becoming richer and richer in experience, and still just steadily moving towards the end of our line. Everything is stacked and packed away at the end. Then what? Then nothing, no motif for our movements, nothing to make sense of the succession of events, but in the fact of the record, in the volumes of traces, marks, and impressions, that are part of life, and yet not exactly it.

Majoli’s woodblock prints move us to think into the recorded image as a form of intimacy found within a lost past. It bears noting that the word ‘record’ itself alludes to an inward turn: the ‘re-’ marking on memory, revised, and ‘-cord’ hailing the Latin ‘cordium’ for heart. Life, in the record, is built-up backwards, inwards—as inverted image, holding a place within the past. Still, the record only exists to us as emblem, image, icon, and so is shown to belong to the present. That is, it reflects not life, but life with the blanks left in: x marking the spot. Like initials scratched into bark, meaning is signified as inlaid. The printed image reverses contour as pure space, that contains and conceals meaning in volume, inside. It reflects on what is currently present. Like so, the recorded image takes place in the moment of its encounter. It pours attention and meaning into what passes through, across, inside, per what Catherine Ingraham has called “the power of the abbreviation (the opening provided by the shortfall, the epigram, the mark).”

Consider what is contained in Majoli’s names, titles: (Blueboy) Rameses (2023), (Blueboy) Tom (2023), (Playguy) Ben (2023). The proper names are stand-ins for a parenthetical place in time, recovered in the act of evocation, in the byline. These men no longer exist but in the fact of the record, in the moment liberated from time. Names act analogical to the printed image, holding space inside inverted lines that pour with distance, volume, interior. The absent contour stands in for everything that is not the contour, that could never be the contour. Omission turns us to the tactile, the textured thing of a life. Fireplaces, brick walls, and flowers, like bodies, hold their own in absentia of clear outline. Figures share an emotional valence with the softness of space.

For the record: Hannah Hoffman’s house was designed by architect Paul Williams (1952) who was said to have drafted all his blueprints upside down, as inverted images. It was, on one hand, a gesture developed in anticipation of clients who felt uncomfortable seated next to a Black man. But Williams called it his ‘sleight of hand’: a trick performed to open space between himself and his clients, drawing a relation, and so connecting through common lines. This particular inversion marks the crucial politic in Majoli’s vacated line. The artist is concerned with all that’s ferried in the omission. But she also knows that to fill the gaps would be a mistake. The recorded image faces us to lost information, irreparable rifts, cut connections, wounds, breakups, and pauses. Things lost, and disoriented in time. And in all these absences, a sudden knowing. To fill the space would betray the loss, the life. We strain to recover the blanks in history—and risk falling into the abstract.

In other words, what the record shows is what it holds: passing desires, the fleeting moment, changes of heart. Majoli opens the line as a space at once abstract and articulated: the record made fully present.

– Sabrina Tarasoff

Monica Majoli was born in 1963 in Los Angeles. She is primarily a painter deeply invested in the traditions of the medium while exploring subjects tied to sex, sexuality, power, and alternative lifestyles such as BDSM. Her work often depicts scenes of sexual fetishism, a theme that serves as a decoy for larger underlying political concerns. In her earlier works Majoli utilized traditional oil-painting techniques to render detailed and realistic homoerotic scenes that included her own body. While these works were pointed and confrontational in their imagery, she describes them as being less about the acts they portray and more about the social and psychological consequences and context of such acts. Since 2015 she has been developing a series titled Blueboys, named after one of the earliest gay men’s magazines in the U.S., founded by Donald N. Embinder and published in Florida from 1974 to 2007. In these works Majoli scales up images culled from the magazine through a white-line woodcut technique developed in Provincetown, Massachusetts, in the early twentieth century, primarily by women printmakers who were influenced by traditional Japanese woodcuts. Majoli has had solo presentations at Galerie Buchholz, New York (2019); Air de Paris, Paris (2014); Gagosian Gallery, New York (2006); and Feature Inc., New York (1998). Notable group exhibitions include Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2020, 2007); San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2017); Museum of Modern Art, New York (2011, 2009); and Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2006), among others.

Her work is in the public collections of Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; The Whitney Musuem of American Art, New York, NY; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA; The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; Pinault Collection, Paris, France, The Grunwald Center, Hammer Museum.